Table of Contents

Poetry

Zoe Canner

Claiming All of Our Dead

Be a Better Listener

Street Introvert

Stephanie Valente

Shalmali Sankpal

Yi Jung Chen

Short Story

Saeed Ur Rehman

Red Shorts

Joe Pan

Flash

Shawn Eichman

Naukarani

Tristan Skogen

Magpies

Photo

Shelbey Leco

Full Size R

Untitled 1

Untitled 2

Video

Eri Kassnel

Artwork

Jon Courtier

I’ve Been Absent

Emanuela Iorga

The Egg-Bearing Serpent

Industrial

Fatima Tall

Untitled Artwork 9

Untitled Artwork 6

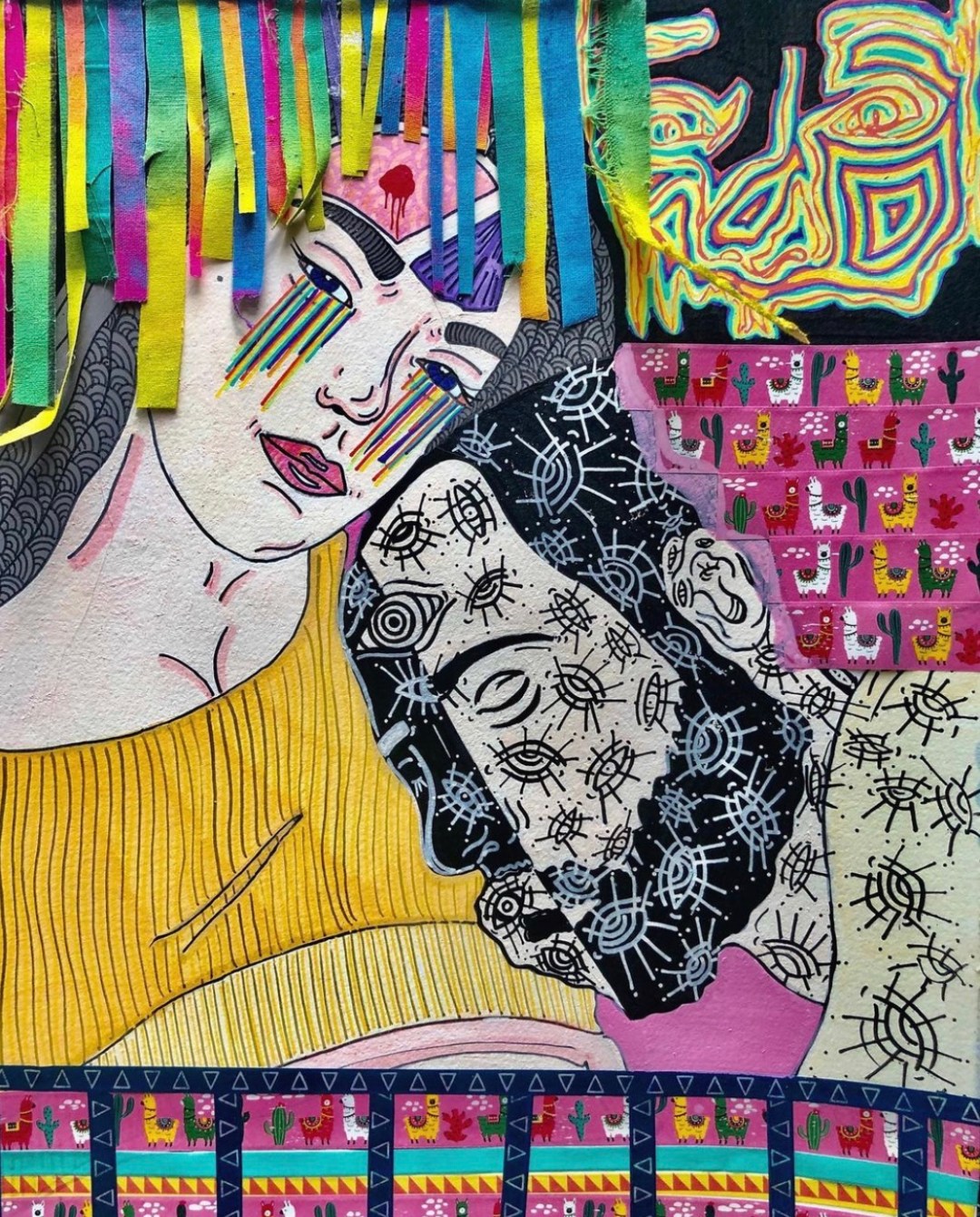

Mixed Media

K. Johnson Bowles

Jerome Berglund

Claiming All of Our Dead

for Richard Hake and our many New Yorkers to remember

Zoe Canner

This is the second plague of my lifetime.

My first doctor died of AIDS when I

was two. My mom retells the story of

what he said right after I was born. My

doctor sat with my mom, checking in,

describing me with pleasure. He said,

“Your baby is healthy and lovely. And

what stunning eyebrows! Maybe it’s

Maybelline! Maybe she’s born with it!

Zoe is a perfect beauty. You did so

well, Adrianne! And she helped. That’s

why this birth was so fast—Zoe was

ready and she worked with us.” My

mom was in a shared hospital room

in the maternity ward at Roosevelt

Hospital in Manhattan. There was

another woman recovering from labor

on the other side of a privacy curtain

and a few beats after my doctor left the

room, the voice of that woman floated

out to my mom. “Who WAS that??”

She asked. And my mom said, “My

doctor. He’s wonderful.” “That was

your doctor?!” Incredulous. “I wish

my doctor spoke to me like that!”

My mom softly weeps. Now.

Thirty-eight years later. For our

doctor and his perfect beauty. The

gravity of each loss is too much—

too heavy to hold—my dears—so

we sway, so we buckle, so we lean

on one another and stumble. And, if

we’re lucky, get back up for more.

Sleep Well, My Love

Eri Kassnel

Eri Kassnel

Eri Kassnel is a video and concept artist, living and working in a small Bavarian village near

Augsburg / Germany. She was born 1973 in Timișoara / Romania. Her family emigrated to

Germany in 1978. She studied “Restoration” at the University of the Arts Bern / Switzerland

and “Interactive Media” at the University of Applied Sciences Augsburg / Germany. Today she

works as a freelance artist and lecturer at the Faculty of Design, Augsburg University of Applied

Sciences.

Her works have been shown internationally, i.e. FILE in Sao Paulo / BRA, International Video

Art House Madrid / ES, OPEN ART Biennial Örebro / SE and others.

TAOS

Stephanie Valente

my legacy is

oil-shaped

i am blood-colored

smoke

the old man

grabbed my hand,

and said: “the thing

about this town is

wine, women, and turquoise.”

Full Size R

Shelbey Leco

Be a Better Listener

Zoe Canner

i will not grow accustomed

to numbering &ranking

the dead. each name, each

number, pricks my skin.

&when i hear about a

child getting punched in

the face for being

asian-american in this

year’s america because the

clown promoted racism,

scapegoating, &death,

the bile rises through a

constricted cavity, up

my esophagus, &my

mouth tastes bitter like

kerosene. a dizzy spell

begins; as my spatial

vertigo kicks in, i level

a flat hand to the wall to

steady myself. my eyes

grow glassy &my heart

rate quickens. no matter

how much bigotry we

know exists, it’s never

incorrect to be upset by

something upsetting. i

soften here. i will not

be changed by him,

by this. i will not

thicken my only skin

for the norm of excusing

hatred. &it’s not up to

women to fix how the

world hates women.

ditto every human

being othered, to the

power of infinity.

Red Shorts

Saeed Ur Rehman

The old man sitting at the next table was hollering at the waiters. They had served him a cold cup of chai. The manager walked over and placed a hand on the grumpy man’s shoulder.

“Everything will be okay, sir. Just calm down.” The old man halted his loudness charade but kept on moving his lips, probably cursing the entire world.

“Sir, do you smoke?” said the manager.

“I do.”

“Here, have a cigarette. Go outside. Have a smoke. When you are done, come back inside and you’ll have the hottest cup of chai in Islamabad waiting for you.”

The old man accepted the peace offering, got up and started walking out. Just before pulling the door open, he stopped and patted his pockets. He was wearing a thick woollen coat and red bermuda shorts. His upper body was dressed for winter and lower for summer. He patted some more pockets as he turned towards me.

“Young man, do you have a lighter?” He asked as if everybody in the world owed him a lighter. I handed my Zippo over. He got excited and thanked me in four or five different languages in near-native pronunciation—obrigado, merci beaucoup, danke schön, shukran, gracias— and walked out. I was intrigued. He was standing on the footpath and I could see him pulling at his cigarette. I told the manager to set up two chairs outside and picked up my cup of chai and joined the sartorial oxymoron outside. Across the road, F-9 Park was turning deep orange. Autumn in Islamabad is painfully beautiful. The old man was standing with his back towards the Margalla Hills.

“The wind coming from the mountains is very cold,” he said in a guttural voice.

“You need to cover your legs too in this weather,” I stated the obvious. A waiter set up two chairs and a folding table. We both sat down.

“They are life-proof legs.” He patted his gnarled knees.

“How did they do that?”

“What?”

“Your legs. How did they become life-proof?”

“When you’ve walked away from every disaster unharmed, you start thinking your legs are special.”

“I can see some varicose veins.”

“I stood around for days watching things being built. I used to be a designer of petrol stations. For some years, I was the only one in Lahore who could meet the safety standards of the ISO and Pakistani regulatory authorities. From underground storage tanks to retail points, I was the man you had to consult. It all went wrong one summer at a petrol station which I had designed.”

“What do you mean?”

“Can I sponge a cigarette off you?”

“I handed him the pack. He pulled one cigarette out and put the pack in his pocket. When I stared at the invisible cigarettes in his pocket, he laughed as if getting caught for being too clever was normal for him. Then, he gave me the pack back.”

I also lit one. Two cups of hot chai arrived. We started sipping. “Go on,” I said.

“Look, you know, petrol is a very volatile liquid. This retail station that I had designed had its underground tanks built in winter. The vapor pressure and the vents had also been tested in winter. I’d told everybody to wait for the summer. Vapor control devices should be tested in summer before the storage system is considered safe.”

“Makes sense but it is all new to me. Just tell me what happened?”

“The owner was greedy. He wanted his investment to start paying back as quickly as possible. But you can’t disrespect ancient life forms, animals, and plants.”

“Ancient life forms?”

“Petroleum is the essence of ancient life forms. I have lived on offshore and onshore drilling rigs and travelled along the delivery vehicles and pipelines. Pakistani and Gulf summers go beyond all the Europeans and American safety standards. In California, where the temperature rarely goes beyond 36 celsius, you get more than 10 pounds of vapor per 1000 liters of petrol. Above 36 celsius is a heat wave for many Westerners. In Pakistan, selling petrol in a city like Larkana, one of the hottest places on earth in May and June, is something else. Even the attendants are high on the fumes coming from the dispensers and the vents. Anything can happen. Ancient bones are eager to cast their spell.”

“That’s poetic but please tell me what happened.” He was getting excited talking about petrol. I wanted him to tell his story.

“What happened? A customer had left the engine of his ice-cream delivery van idling near the vent pipes. Something sparked. Boom.”

“You must be kidding.”

“Everything I am saying is true.” He slammed the cup on the table to assert and continued. “The station was up in flames in seconds. Ambulances and fire trucks came blaring their sirens. By that time, some passersby had pulled the burning bodies out from under the melting fibreglass canopy. Four attendants, two customers, and one manager were lying on the road half-charred. Only one attendant survived.”

“That’s horrible.”

“The owner filed a case against me and hired some of the best lawyers in the country. He also had the law and energy ministers on speed dial. I showed my emails in which I’d asked for more safety tests. But nothing worked for me. He walked unscathed. I had to pay hefty sums to him and to the families of the victims. It was a scandal. If you watch the news or read papers, you couldn’t have missed it. You probably know about it already.”

“No. I don’t. I was in Phnom Penh for some years.”

“I had to sell my business and house. I declared bankruptcy when I was left with ten thousand rupees. My wife and sons turned away from me. They couldn’t bear the shame. I moved here to escape the disgrace and now live in a small rented place in Seri Saral.”

“Where is that? I’ve never heard of it.”

“It is about eight kilometers from here. It is the cheapest place I could find.”

“I don’t know what to say to you and if any words can console you.”

“I’ve experienced public disgrace and loss. It has changed me. Now there is nothing left to lose. I can be as shameless and selfish as I want. What’s your story?”

“Very simple. Divorced. I live alone and work for an NGO. These days I am building a database of organizations that can be mobilized if a natural disaster strikes in South Asia. What do you do these days?”

“I watch people drink chai and sometimes talk to them. I live on the largesse of some former colleagues. Some of them still seek my advice informally.”

“That’s great.”

“I need to get going. I can still pay for your chai, young man. Thank you for listening to my story.”

“I think you should let me pay.”

“This is on me.”

“You should save your money.”

“I haven’t got anything to save or lose.” This silenced me. He paid for both of us and walked away after shaking my hand. I didn’t know what to make of his story.

_____________________________________________________________

I met him again after several days. The red shorts had given way to old corduroy trousers and his upper body was covered with a loose overcoat which was wrapped like a shawl. The manager gave him a couple of cigarettes. I offered him a plate of Cajun potato wedges which he accepted with thanks in only one language. I felt he was not going to pull through the winter.

“How do you get around?” I wanted to find out if he had the means to survive for some months. I was getting a handsome salary and had no dependents. I wanted to be helpful.

“I have an old motorbike.”

“In this weather, you ride around on a bike?”

“When it is too cold, I rely on the kindness of strangers.”

“You hitch hike?”

“I just stand at bus stops until someone offers a ride. I usually have nowhere to go.”

“Interesting. How did you get here today?”

“Today an employee of the National Archives offered me a lift in his car. He was kind enough to take a detour and drop me right outside this cafe.”

“And I can drop you back at your place.”

“Gracias, amigo.”

“How many languages do you speak?”

“I can order food and drinks in seven languages. ‘Uma cerveja grande para todos, por favor’ can be very handy if you are celebrating something on an oil rig in Brazil.”

“Do you want to eat or drink something? My treat.”

“No. I’ve had elegant sufficiency today. We can go.” We both walked to my car. The wind made me shiver. I looked at the old man. He walked briskly with his arms folded on his chest. When we got to the car, I opened the door for him to show courtesy and he acknowledged it by bowing his head. I felt he must have been a suave negotiator when I saw him genuflecting before seating himself. I turned the heater on and set the destination to Seri Saral on the navigation panel. It took fifteen minutes to reach the outskirts of Islamabad. Bright streetlights and macadamized roads disappeared as we took the turn to the basti he was living in.

“Park your car somewhere. We have to walk the rest of the way. And if you do not smell nervous, you are safe.”

“I am here to only drop you off. And what do you mean by smelling nervous?”

“I want to show you my place. I think dogs can smell anxiety and that’s how they figure out intruders.”

“How do you know that?” I asked as I parked at a dry spot among the puddles of sewage water.

“I must’ve read it in some scientific magazine. Then I tested this information when someone told me that dogs in graveyards like to eat human flesh because they can dig out dead bodies. I went to a graveyard to see if dogs that are fond of eating dead homo sapiens bark at me. I had a stun gun with me in case my experiment turned ugly.”

“Why?”

“Once a tinkerer, always a tinkerer. These days I don’t have access to my usual tools. So I have started doing things with whatever is available for free. Trees, dogs, insects are under observation. I don’t hurt anything. Sometimes a lightbulb and moths are all you need to test some interesting theories.”

We walked through dark and uneven alleys till he stopped in front of a shuttered shop. I thought he was going to break into a shop but he stooped down to open the lock and pulled up the shutter.

“Let’s get to your place, man.”

“This is my place.”

“You live in a shop?”

“I do. Nobody was willing to set up a business in it so the landlord gave it to me for living. It is an elegant solution.”

He turned on a sickly, yellow light. The room was a hymn to dust. He sat down in the only chair in the room and pointed the bed to me. I sank in the smell of defeat, Vicks VapoRub, and old age. In one corner, a leather suitcase had its countless airport tags turning into cobwebs.

“Do you have a washroom here?”

“No. When I’m here, I have to go to nature to answer the call.”

“Ah. Is that why you are always at that cafe?”

“Yes. During the day, I spend time at places where I can use the washroom for a cup of chai. At night, I can go to the fields behind the basti. You have to make do.”

“What about your other needs?”

“Yeah, they are there. I can’t bring a date or a lover here.”

“How do you solve that problem?”

“There is no solution. I just drive around with people if I meet someone interesting who has a car. I can’t bring a date here.”

“If you ever want to meet someone at a safe place, you can come to my flat. It is in one of those high-rises in F-10. People don’t mind a lot of things there.”

“I am thankful for your generous offer. I might avail it one day.”

“Sure.” We exchanged numbers and I left.

_____________________________________________________________

A month or so later, I am in the lift, going up to my flat. A shabbily dressed, middle-aged woman is also in the lift and she does not seem to know which floor she needs to go to. As we both are being pulled up, I catch the woman sizing me up. When I look at her, she holds my gaze and smiles.

“Sahib, do you need a maid at your flat?”

“What can you do?”

“Everything. Anything. Whatever you desire.” The way she says the words makes me think of the old man and his needs.

“What do you charge? I am not asking for myself. A friend of mine, an old man, can use a little happiness in his life. I hope you understand what I am hinting at.”

“I get you. You want an old man to sing happy songs. It will be 1000 Rupees per hour.”

“That’s okay. I live on the 9th Floor. You will have to wait till he arrives.”

“Sure.”

I open the door and offer her a seat in the lounge and put my briefcase in my room. I dial the old man’s number. He picks up. I tell him about the encounter in the lift and ask him to come. He asks about the price. I tell him not to worry it is a gift. He insists on knowing the price I have agreed to pay. I relent. He says he will be with me in fifteen or twenty minutes. I hang up and go to the lounge. She is checking out my flat. It is so sparsely furnished that it is mostly space. One sofa in the lounge. One study desk and chair. One single bed in each room.

“I can offer you chai or water while we are waiting for my friend. That’s all I have at the moment.”

“Nah, sahib. I am fine. How long will it take for your friend to reach here?” She looks at her mobile for time.

“Do you have to go somewhere else after this?”

“Maybe I can find another customer after this.”

“Have you explored this building before?”

“Yeah. But I am not the only one cruising in these buildings. There is a lot of competition.” I like her disarming candor.

“When do you start your day?”

“Around ten-thirty in the morning. That’s when the offices are open or jobless men are at home and their wives have gone to work and the children are in school.”

“That’s very shrewd.”

“What can we do, sahib? I have a good-for-nothing husband and have to feed four children.”

As I try to separate fact from fiction, I say, “Do you also work as a maid?”

“No. That’s just a good way to start a conversation. There is no profit in being a maid. You can earn twenty thousand rupees a month if you work your butt off. This way I can make more.”

“What about the police? Do they ever bother you?”

“No problem. The policemen in this area just want their flutes polished for free. Or they can take their share if I have earned something. That’s all.”

“That’s hard.”

“Nobody is saying life is easy.”

_____________________________________________________________

There is a knock on the door as we run out of things to say to each other. I open the door and the old man is standing there with another shabbily dressed woman who is slightly younger than the one sitting in the lounge.

“Who the hell is she?” I ask him in English so that both of the women don’t get what we are talking about.

“I met her in the lift while coming up. She has agreed to sleep with me for 700 rupees. I know you said it was a gift. But I tried to reduce your burden.” He waves me aside and walks in and the young woman follows him.

Now there are four people in the lounge. The young woman looks at the middle-aged woman already sitting in the lounge and recognizes her. They both are livid about meeting each other in my flat.

“What are you doing here?”

“What are you doing here?”

“This old man brought me here.”

“This sahib brought me here.”

I look at the old man and he just shrugs as the women both are staring me down.

“Who will pay me?” The older woman demands.

“I will pay. It is a gift from me to my old friend here.”

“Don’t pay 1000 to this old lady. This one is younger and cheaper.” The old man is talking as if he was deciding between two machines. I try to calm everyone down.

“Sahib, what is this?”

“Don’t worry. I will give you some money for wasting your time.” As I say this I feel I have insulted her. Or maybe the old man has insulted her. She gets up and marches out of the flat, banging the outer door behind her.

The old man looks at me with a celebratory glint in his eyes. The world is following his plans. He grabs the young woman by the wrist and disappears into a bedroom and bolts the door. I am standing in the middle of the lounge and my head is reeling. After two minutes, the door unbolts and the young woman marches out and the old man is trying to pull her back.

“I can’t do what he wants me to do.”

“What’s going on?” I look at the old man.

“This old man has watched too much porn. He wants to do weird things.”

“I am an old man. I cannot get it up without some foreplay.”

I look at both of them.

“I do it the good old way. That’s what our deal was. It was not for my mouth or ass. You have not bought my entire body with 700 rupees.” She is trembling with rage. The old man tries to hug her but she is not having any of it and pushes him away. She stares at him for some seconds and then she also marches out of the flat. She also bangs the door shut behind her.

Now the old man and I are standing in the lounge looking at each other. I just shrug and fall on the sofa. The old man looks at me.

“Everything was going fine till you thought of saving some of my money.” I say to him but he is not listening. Instead, he is checking me out.

“So many young men are gay these days. Don’t you have any such proclivity?”

I stare back at him, shocked. And then I pick up my phone as if I was going to call help.

“I think I’m going to walk out of another disaster unharmed,” with that, he hurries out of my flat.

Saeed Ur Rehman

Saeed Ur Rehman (PhD, ANU) has held a postdoctoral fellowship at ZMO, Berlin. His work has appeared in Mississippi Review (online section, which is now archived at Blip Magazine) Cultural Dynamics, Kunapipi, The Historian, The Foreigner, The Herald, and Journal of Research (Humanities). His sources of inspiration are André Gide, Georges Bataille and Jean Genet among others. He can be reached at contact[at]saeedurrehman[dot]com.

Returned Expat

Stephanie Johnson

Me dices que

These languages

That I’ve breathed in

Por tantos años

Gereksizdir diyorsin

Bende cevap veriyorum:

Fuck you.

Translation:

You tell me that

These languages

That I’ve breathed in

For so many years

Are useless; so you say

And I answer:

Fuck you.

I’ve Been Absent

Jon Courtier

Jon Courtier

Jon Courtier is a comic artist, writer and programmer living in Brooklyn. His work focuses on the intersection of being P.O.C, racially mixed, queer and autistic.

He spends his time working on comics, hanging with friends and wrestling.

Ritual

Shalmali Sankpal

Wash your hair.

On your scalp lie days of dirt, oil and settled regrets that need to go away.

Condition the edges.

Its okay to have rough days and hear mean words. The blows will soften with time.

Don’t count the hairs that have fallen.

New opportunities will always show up.

Wrap your head in the towel.

Sometimes the thought spiral can be contained.

Wipe your face and body with different towels.

It helps to categorise and prioritise.

Squeeze a coin size amount of moisturiser and sunscreen for your face.

The self must be protected at all times.

Slather some lotion onto your body.

Dry souls tend to itch for love.

Put your clothes on.

You will be different people on different days. Know that you hold multitudes within.

Accessorise.

A few bright moments can hold the darkness at bay.

Spray some perfume on the base of your throat, under your ears, arms and on wrists.

Remember who you are.

Shalmali Sankpal

Shalmali is a lover of art, literature and everything in between. Her writing explores the crosscurrents of identity, loss, longing and the self. She currently works as an English Teacher in Mumbai and dreams of becoming a writer one day.

The Egg-Bearing Serpent

Emanuela Iorga

Untitled 1

Shelbey Leco

Naukarani

Shawn Eichman

The moon rises over the Western Paradise of Sukhavati. The Enlightened One Amitabha, supreme teacher of this realm, sits in his palace of white walls and vermilion-painted sandalwood pillars, looking out over his garden bathed in silver light. Gandharvas float above him, singing songs of wisdom to the beat of drums and gold cymbals. Two dancers perform before him, diaphanous silks swirling in perfect circles. Their raised platform is surrounded by a heart-shaped pond fed by streams filled with budding lotuses. The Dragon King rises from below the water, kneeling before Amitabha to request that the welcoming ceremony begin. Amitabha smiles as a luminous ray emits from the curl of hair on his forehead, and flowers rain from the sky.

Naukarani groans. Why does he insist on doing that? Who exactly does he think will clean it up? She reaches for a vacuum and starts to sweep the fallen blossoms. The lotus buds open to reveal immaculate infants, the newly reincarnated souls of those whose sincere pursuit of understanding in their previous lives has led them to this blessed land. Naukarani rolls her eyes. Immaculate—right. It might go in as nectar, but it still has to come out the other end. You try changing ten billion diapers every day. She continues to sweep with one arm, while another reaches for one of the infants, and another, and another, until all thousand of her arms are full and all ten of her faces are looking down on cooing bundles. Still, it is worth it for moments like this. One of them spits up on her sarong. Sigh. ‘The best medicine is wisdom’ she mimics sarcastically. What I wouldn’t do for some Pepto. She gives the child a placebo to suck on, hoping that will calm its stomach. She thinks back to her college days as an ogress, when she used to eat children instead of nursing them. She knows she fell in with the wrong crowd, and she is grateful to Amitabha for helping her get clean. All the same, I can’t be blamed for an occasional urge to pop one of the little monsters in my mouth. She grins wickedly.

As the moon sets on another night in paradise, she heads to the employee lounge for her break. She takes a bottle of rosé out of the refrigerator, pours herself a glass and sits down. The bottle stays on the table. It’s ok, she explains to herself, tonight I’m practicing Tantra. She lights a cigarette and reaches for the remote. She puts her thousand feet up on the table and flips through the channels until she finds ‘The Real Apsaras of Sukhavati.’ All things are impermanent, she muses, including this rosé. She reaches for the bottle and pours another glass.

Shawn Eichman

Shawn Eichman writes underwater off the coast of Honolulu. He sometimes comes on land to learn from banyan trees and play shakuhachi in a bamboo grove for an audience of birds.

Industrial

Emanuela Iorga

Emanuela Iorga

Emanuela Iorga is a filmmaker, artist, and screenwriter, who lives in Chisinau, Moldova. Art represents for her a recently rediscovered passion, following a series of world and inner changes. She was previously published in Jet Fuel Review, Pithead Chapel, Beyond Words, Please See Me, FLARE, and Up the Staircase Quarterly. Her work can also be found at https://manolcaincosmos.wordpress.com.

The Embodiment

Joe Pan

The moment the woman in the raincoat walked through the front door, Hannah knew she wasn’t her real mother.

Yes, this person looked like her mother, but something was missing—gone from the eyes was that familiar glint of mirth, that natural sense of wonder, of being happily surprised by everything. This woman’s eyes were as purple and sunken as dead clams. She wore no makeup and her hair was a straggly mess. Besides that, where were her bracelets, and Grandma’s gold watch? Even her wedding ring was missing.

Three days earlier, Hannah had woken to find the babysitter, Anne, cooking her a feta and broccoli omelet. Her parents had left in the night for reasons Hannah didn’t fully understand, but Anne promised they would return soon. In the meantime, she would look after Hannah and they would play Chutes and Ladders together and go to the park to feed ducks and watch tons of movies, which they did. Whenever Hannah asked where her parents were, Anne would say they would be home soon, and try to turn her attention to something else.

Hannah was busy with a coloring book when she heard the car pull up. The screen door sucked opened and there stood her father, and beside him, a stranger—a person who might have been an aunt, if her mother had a sister, which she didn’t. Her father greeted Anne with a nod and a thank you, but the woman stared straight forward, ignoring Hannah on the sofa and their skittish Pomeranian, Macho, who yipped and cowered beneath the kitchen table. But there was something in Macho’s reaction that helped justify the feeling Hannah was having. Glancing over, her father offered her a weak smile before guiding the stranger down the hall and into her parent’s bedroom, closing the door.

Hannah was more than a little frightened—whoever or whatever this creature was had fooled her father with its unconvincing mask, or worse, had somehow forced its way into her mother’s body. She didn’t know who to call or tell. Her grandparents? The police? Her mother’s phone, left behind in their midnight departure, lay on the kitchen table. She stood on her tippy-toes and pulled it over and locked herself in the bathroom and dialed 119, but nobody answered.

“Your mother needs rest,” her father explained over pizza that night, after Anne had left. Hannah wanted to wrap herself around his leg and warn him, but she sensed the intruder could read minds, even from behind the bedroom door. “She’s been through a lot. We’ll be quiet and thoughtful, okay? It’s going to take some time.”

“When is Richie coming home?” asked Hannah directly, worried for him as well.

Her father’s expression turned. Laying down his slice, he reached over and enveloped Hannah’s little hand in his on the table, sliding two fingers up the bridge of his nose and under his glasses. There would be no answer.

An hour later he was passed out on the couch, and Hannah, being a brave little girl, decided it was time to face the creature. She snuck down the carpeted hallway and stood before the bedroom door, watching the light by her toes for shadows. She took a deep breath and slowly turned the knob, grimacing at the click. Then pushed the door slightly and peered through the narrow slit.

The creature was in bed, propped against a mountain of pillows. The TV was on but there was no sound. When Hannah pushed the door open a bit further, the creature’s head turned and its black eyes fell upon her, causing Hannah’s breath to cinch in her lungs.

“Hey baby,” said the creature. “Come on in, it’s okay.”

Pushing through the terror, Hannah stepped into the room. Fleeing now would give away her thoughts, and she had her father’s safety to consider.

“I’m sorry things have been so hectic around here,” said the creature. Its face was red and puffy, its eyes dark and lost. “Mommy just needs to relax some. You’ll take care of Daddy, won’t you? While Mommy relaxes some?”

Hannah stepped closer to the bed, fully on guard. “Where’s all your bracelets? And your ring?” she asked. “Where’s the watch Grandma gave you?”

The creature looked at its hands, as if for the first time. “I don’t know. I guess your father has them.”

The fingernails were raw and chewed, she noticed. Her real mother’s nails were meticulously kept. “You’re not my mother, are you?” Hannah asked, stepping back.

The creature’s eyes hardened with consideration, then widened and softened. “Why would you say that?”

“I can tell,” said Hannah. “You aren’t, are you?”

“Maybe not,” whispered the creature. “Maybe I’m nobody’s mother.”

Hannah ran from the room.

That night she slept on the floor by her father, pulling off the sofa cushions and plugging in the seashell light nearby and placing Jiminy Wiggles the one-eyed Pig in the hallway to stand guard.

She hadn’t told her father what happened, and neither had the creature, apparently, for Hannah was asked to bring coffee to the creature in the woman-suit, along with a badly toasted bagel.

She found the creature in the same position as before. This time the TV’s sound was on, but low. The curtains remained drawn, the room brightened by a small lamp.

Its dark eyes followed Hannah as she placed the coffee saucer and the plated bagel on the nightstand.

“I’m not hungry,” it said, “but thank you.”

“I want to play a game,” said Hannah, who’d been plotting all morning. “I’m going to tell you something about you, and you’re going to tell me something about me, something that only you know.”

A small smile lit upon the grim corners of the creature’s lips. “Sure. Fire away.”

“Your favorite color is purple,” said Hannah. This was true, and she knew it—much of her mother’s wardrobe was purple.

“Yes,” said the creature. “And yours is blue.”

But anyone could have guessed that, Hannah thought, and reset her stance on the carpet—sure she’d have to run. “You were born in Connecticut.”

The creature sadly nodded, looking down. After a moment she said, “And you were born in a little hospital in Maine, while we were on vacation. You came earlier than expected. They put you in a little glass house, all by yourself. You looked like a bunch of plums all smooshed together.”

Hannah didn’t understand the plums bit, but it was true she was born in Maine. She was born pretty muched, as her father like to say, calling her a miracle whenever he told the story to friends.

“Your favorite food is tiny oranges,” said Hannah.

“It’s not,” remarked the creature from some faraway place.

Hannah was ecstatic, having caught the creature in a lie. “It is, it is!” she exclaimed. “Your favorite food is tiny oranges!”

The creature’s dead-eyes didn’t waver. “No, it’s not. It’s just what your father likes to get me. And I eat them, because I love him. It was our first date—we were on the beach, and I was hungry, and there was a fruit stand in the parking lot selling clementines. We were so young. We thought it would all be so easy. He was in love, and I was a stupid teenager. We think all these decisions don’t mean anything, that you can just change your mind later. But you can’t. Not always. It’s all so…solid. A lot of times it feels so fluid, but most of it is very, very solid.”

“I know you’re not my mother,” said Hannah. “My mother loves my father.”

This didn’t seem to affect the creature, who spoke as if from a trance. The color of her skin was dreadful in the lamplight. “You’re right,” the creature confirmed. “Your momma’s gone.” Tears were appearing at the corner of its eyes. “I wish she were here. She would know what to do.”

Hannah was very upset by this news and charged from the room yelling for her father.

She found him at the kitchen table, crying in his hands. Hannah had never seen her father cry before and stopped short of entering the room. It scared her and she began whining nervously. Her father regained himself and hurried to her side, cradling her in his arms and making soothing noises as he rocked from side to side. He told her everything was going to be okay, and that Anne was coming over soon to fix her lasagna and pickles, her favorite. Anne was going to stay with them again for a week or so, cooking and cleaning, while he took care of her mother, who was very sick and needed his attention.

“It’s going to be okay,” he promised, but his hands held a slight tremor, and his voice wasn’t at all reassuring.

It continued to rain for three days straight, stripping the fall colors from the sycamores and rushing them down the street and blocking the storm drain. Hannah read books by the window and colored a lot and played with Macho when she was bored and helped Anne snap the ends off green beans and pull tassels from corn. Her father reappeared for meals but mostly kept to the bedroom. Hannah was sure he was now completely under the creature’s control and there was nothing she could do about it. Anne didn’t seem to find anything unusual. All the other adults Hannah knew were only available by phone, which had mysteriously disappeared from the table.

That night Hannah heard the creature yelling in the back room, with her father shouting and begging for it to calm down. Anne turned the TV volume louder, pretending not to hear, and that’s when Hannah realized she was brainwashed, too.

On the fourth morning her father left to pick up medicine for the creature, and while Anne was vacuuming in the living room, Hannah snuck back and slowly opened her parents’ door.

The creature was asleep—she could hear it snoring. But the snores were full of mucus and wildly inhuman, a rough dragging of air. And Hannah couldn’t be sure, because of the covers, but it seemed the creature now had more than two legs—three or four at least. Its breasts were wobbly looking under the thin blue gown and its stomach was chubby but also flattish, the skin all loose.

The room stank of sweat and cigarettes, and Hannah pinched her nose and breathed through her mouth. There were lots of medicine packages on the nightstand, some ripped open, or with their bubbles popped, and tiny orange bottles with the lids screwed on improperly. That’s where she spotted the pack of cigarettes, another clue, since neither of her parents smoked. She only meant to move the glass of water over a little bit to get a better look at the creature but accidentally knocked it over. The creature shot up, as if from a nightmare, and caught her in its sight. For a moment the creature looked positively terrified.

“Where…where?” it muttered, feeling around the bed. Then it stopped to glare at Hannah. “What’s happening?”

“I was cleaning up,” said Hannah, “and accidentally dropped a glass.”

“Oh,” said the creature, feeling for its bearings. “It’s okay. Everything’s okay.”

“Where’s Richie?” asked Hannah.

These were magic words—for the same spell they worked on her father, they worked on the creature. Its mouth slacked open, yet no words came. It seemed not to understand what had been said.

“Where’s my brother?” demanded the little girl.

Within moments the creature’s breathing turned funny, escaping in short little hiccups. It faced forward and clutched its chest, then bellowed so loudly that it startled Hannah, who matched its cry. The vacuum cleaner shut off in the living room and footsteps charged down the hallway. Anne rushed to the creature’s side as it wrapped itself in covers and pulled pillows into its face.

“Hannah, leave!” shouted Anne. “Honey, go read, go do something!”

Hannah fled.

Instead of seeking out the comfort of bed or burying her face in the couch, she ducked into her mother’s old office, slamming the door behind her.

The room was small and blue and washed in failing light. A brand new crib rested in the corner where her mother’s drawing table once stood. There was a desk Hannah knew was full of tiny clothes and the ceiling pricked with little stars stuck that glowed green in the half light. Hannah knelt down and crawled under the crib and waited there until the moaning stopped. She heard Anne close the door and begin calling out her name, searching the house. But Hannah wouldn’t come out.

It wasn’t long before Anne came to check the room—hesitant, it seemed, to make much noise. Hannah expected her to get down on her knees but Anne just squatted by the door and smiled weakly.

“Why don’t we go out for lunch,” said Anne. “Picnic in the park. We’ll take Macho to play with all the other dogs.”

The morning was chilly but cleared up nicely by the afternoon and the playful dogs were indeed a wonderful sight—they jumped on each other and nipped at tails and wagged with happiness. It was so wonderful that Hannah didn’t want to go home, and forced Anne to drag her and then carry her back to the car, with Macho in tow.

They found her father in the kitchen, dropping onions and chilis into a crockpot for morita chicken stew. It was the first time he’d cooked since the night they’d left for the hospital. He thanked Anne for her help and handed her an envelope and said he might need her again, if that was okay, and she said she’d be glad to help, anything to take her mind off her dissertation.

After Anne left, Hannah’s father pulled her close, going down to one knee to look her in the eye.

“Mommy’s told me what you two talked about,” he said. “I’m not angry. I bet you have lots of questions.”

“She’s not Mommy,” explained Hannah.

Her father cinched his lips but nodded. “She’s up. I know she’d like to see you. I made her some tea. Would you mind bringing it back to her?”

Hannah considered this. It was clear her father didn’t believe her, or at least wasn’t going to help, so she nodded and reluctantly took the mug of tea down the hallway.

The creature was sitting up in bed, looking out the window. It was the first time the curtains were drawn back. She smiled as Hannah stepped forward, holding the mug out with both hands.

It took the mug and sipped carefully, then said, “I’m here to answer any questions you might have.”

Hannah peeked back at the door. Was this a trick?

“Where’s Richie?”

“He’s in heaven,” said the creature.

“There is no heaven. Mommy told me.”

The creature scrunched its face. Then nodded. “I’m sorry, yes. Yes, it’s true, there is no heaven.”

“What did you do with Mommy?”

“She’s still inside me,” said the creature. “She talks to me. She says she loves you very much.”

“Are you going to eat me?”

“I don’t think so. I hope not.”

“Please don’t hurt Daddy!”

The creature balled its fists and inhaled deeply. “I’m trying not to.”

“When is Mommy coming back?”

The creature looked very tired again. It picked at its nails. “Do you think you could learn to love me, even if I wasn’t your mother? Even if she never returned.”

Hannah shook her head no.

“Why not?”

“I don’t know you,” said Hannah.

“That makes two of us,” said the creature. “But I think you can help bring her back.”

“How.”

The creature peered back out the window. “Why don’t you start by telling me what you know about her. All the little things you remember. Tell me what she likes, what she means to you. Can you do that?”

“Will it work?” asked Hannah.

“Wouldn’t hurt to try,” said the creature.

Hannah found all of this very curious, but if it meant having her mother return, she would try. “She likes zebras, and carnival rides, and small dogs. And old pencil sharpeners with the gears, like the one in her office. It was on her desk, before she moved everything out to the garage. She used pencils for work. She was an architecture.”

“Yes, that’s right,” marveled the creature. “She was an architecture. Tell me more.”

Joe Pan

Joe Pan is the author of six books, including the poetry best-sellers Operating Systems and Hi c cu ps, and was coeditor of the popular Brooklyn Poets Anthology. His nonfiction has appeared in such venues as Hyperallergic, The New Republic, The New York Times, The Philadelphia Review of Books, and Poets & Writers; interviews in the New York Post, Publishers Weekly, The Rumpus, and the Wall Street Journal. He is founding publisher and editor-in-chief of Brooklyn Arts Press, the smallest press ever honored with a National Book Award in Poetry, in 2016. He also serves as the publisher of Augury Books, an imprint of BAP, recently honored with a Lambda Literary win for the Best Lesbian Poetry Book in 2021. Along with his wife, Pan cofounded the services-oriented activist group Brooklyn Artists Helping, dedicated to fighting homelessness.

Untitled Artwork 6

Fatima Tall

Untitled Artwork 9

Fatima Tall

Fatima Tall

Fatima Abby Tall is a Black creative currently residing in Portland, OR. They were raised in rural Idaho but feel most at home in Dakar, Senegal. They graduated from the University of Iowa with BA’s in English and Creative Writing and Gender, Women’s & Sexuality Studies. fatima does not work within one specific discipline. They tend to create art that consorts with spirit and self. You can find their work at LoosenArt, Bottlecap Press, and in AbolitionISH Zine Endnotes.

Street Introvert

Zoe Canner

My fortune said

what is a life

unexamined

solitude is my

friend

and so are you

street lion

I see you eating

street meat

looking at

street art

in the

street heat

patriarchy is a

dying animal

and a dying

animal is the

most dangerous

I’m shedding my

skin again

renegotiating the

term kin again

we will fight

and we will win

again

Zoe Canner

Zoe Canner’s writing has appeared in Angel City Review, Rising Phoenix Review, The Laurel Review, Arcturus of the Chicago Review of Books, Indolent Books, Storm Cellar, Maudlin House, Occulum, Pouch, Nailed Magazine, SUSAN / The Journal, and elsewhere. An alum of CalArts, Zoe was nominated for the Pushcart Prize by Matter: A Journal of Political Poetry and Commentary. zoecanner.com.

Suicide Watch Forget-Me-Not

K. Johnson Bowles

Native Tree-Invasive Tree

Stephanie Johnson

Native Tree

They are seducers those lovely gum trees

the perfume flowing from their groves,

pattered, ribboned bark

twisted arms rising up

to sunbathe.

Stunning crowns of blue-green hair

a cloudy mist among the

matchstick branches

or is that smoke

drifting through the grove

They sigh with pleasure

as things heat up

gum trees crave new

beginnings just like we do

invasive tree

stunning trees

california immigrants

twisting habits

narrow trunks

patterned barks

ribboned surfaces

blue-green leaves

eucalyptus

perfume of forest

drought survivors

fire hazard

life renewers

colonizers

candle bark

living matches

Stephanie Johnson

Stephanie Johnson has spent most of her adult life overseas living with type 1 diabetes and teaching English literature, ESL and Spanish at universities and adult education settings around the world. Her writing usually focuses on the slightly uncomfortable space of the expatriation/ repatriation experience. She has most recently been published in Authora Australis and force/fields, an anthology published by Perennial Press. She is an associate editor at Novel Slices, and is also a judge for NYC Midnight. While she is originally from Toledo, Ohio, USA, she is currently based in Sydney, Australia.

Holding On

K. Johnson Bowles

The Strawberry Moon

Yi Jung Chen

The reddish-pink hue of sky,

reminded me of the streams of light in the river,

your eyes sparkling with ineffable delight.

Draping my jacket over the back of chair,

a comfy action made my heart thump.

Like a shriveled plant,

your face was tortured by the daily drudges.

When push comes to shove,

you are always there with me.

Waiting for the fruit to become ripe,

you walked with me in tandem,

Subtly keeping a distance,

resembling the Big Dipper,

displayed the round-up for my Eudaimonia.

Undulating cadence of tribulations,

moored themselves to our harbor.

The constant drone of rumors

waved their red flags at pitch of noon,

in burning June.

Strutting away in pride,

the gorilla effect took over my mind.

The cutoff point in my blueprint

blazed by your rage till

the crevice split into a rip,

too late for any patches.

Yi Jung Chen

Besides teaching pupils of learning difficulties at Dounan Elementary School of Taiwan, Yi Jung Chen writes poems in English, Chinese and Taiwanese language at her leisure time as well. Provided given the opportunity, she would like to have her poems published by excellent poetry journals and shares her poems with people around the globe.

Explaining Self-Care to the Dead

K. Johnson Bowles

K. Johnson Bowles

K. Johnson Bowles’ artworks focused identity, social justice, and sexual politics. She has been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Houston Center for Photography, Visual Studies Workshop, and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She received an MFA from Ohio University and BFA from Boston University.

THE HOUR OF THE ROSE

Stephanie Valente

in this fairy tale,

my skin catches the thorn.

my blood oozes

like chocolate

you call me petal.

guiding my finger

to your mouth.

i am a white rose

whispering,

drink from me.

baroque blood moon

Stephanie Valente

truth is I lost my soul

a long time ago

before you + your curse

how I ran to you

through Rome streets

hiding my face from saints + god

past the €3 crucifixes

nearly twisting my ankle

skinning a knee,

the blood in my veins

in heat—pure heat

the moon is theatrical,

all cloudy and pastel,

in this night of rites,

my lust is for sale,

your teeth, deeper than god

or water, don’t leave

a drop behind.

Stephanie Valente

Stephanie Athena Valente lives in Brooklyn, NY. Her published works include Internet Girlfriend (Clash Books) and Little Fang (Bottlecap Press). She has writing featured in Witch Craft Magazine, Maudlin House, and Hobart. She is the associate editor at Yes, Poetry. Sometimes, she feels human. stephanievalente.com.

Hammering

Jerome Berglund

Jerome Berglund

Jerome Berglund graduated from USC’s Cinema Production program and spent a picaresque decade in the entertainment industry before returning to the midwest where he was born and raised. He has exhibited many haiku, senryu and haiga online and in print, most recently in the Asahi Shimbun, Failed Haiku, Bear Creek Haiku, and Daily Haiga. He is furthermore an established, award-winning fine art photographer, whose pictures have been shown in galleries across New York, Minneapolis, and Santa Monica.

Magpies

Tristan Skogen

Magpies are the guardians of the roads. Of once-busy intersections, now still. Of the soaring, graceless behemoths that have escaped from the soil and climb into the sky, like buildings of old. Of the cracked, gray scars that line the surface of the earth. Of the remnants of our past.

Nobody has heard of a road without a magpie, at least not here. In this part of the world, every road has at least one—usually more. A nesting pair. A flock of a hundred. Every road has a magpie. Every.

Nobody is quite sure why. Do they know something? Do they know anything? Or are they just. There. Guided by some instinct that not even they understand. What do the magpies understand?

Everybody knows they’re smart. Smart, smart birds, with their trinkets and their toys. We leave them offerings, sometimes. An extra rabbit that we trapped. An old, family dog who passed in her sleep. A bauble from a bygone time that reflects the sunlight straight up, up to where the magpies can see it and be summoned, and in return, they leave us things we might like. Old money. Jewelry that they no longer care about. An interesting rock.

Sometimes, I wonder who is leaving offerings to who.

What do the guardians of the road think of us? Do they think of us as guardians of the ruins? Of the titanic, hollow buildings that rise up from the ground? Of the crumbling houses? Of the burned out, empty stadiums that we call our homes? What are we to magpies? Are we their followers? Their pets? Rivals? What?

Who knows. Maybe not even the magpies.

Sometimes, I wonder if they care about us. The magpies. If they know, deep down, that we made the roads they haunt. Well. Our ancestors. Not us, not anymore. I doubt there’s a person alive, at least in this part of the world, who could make a road.

Sometimes, I wonder who used the roads.

I mean, I know it was us. Well. Our ancestors. The same ones who built them in the first place, but who specifically? Priests? Leaders? Everyday, run of the mill, people?

What went on the roads? I’ve heard people say “cars” and “planes” and “automobiles,” but nobody can tell me what those were. Nobody remembers. Once, I heard a car described as a “sheet metal animal that humans fed bones to as tribute, so that the car would take them places,” and a plane called “a massive, underwater car,” but those both seem unbelievable.

I think our ancestors walked. A lot. Always walking, and the roads were how they got from settlement to settlement. Stomping across that cracked gray scar. I wonder if they had shoes? Sometimes, the roads are so hot from the sun that I can’t bear to step on it, so they must’ve had shoes. Or tougher feet than us.

Sometimes, I wonder if the magpies guarded the roads way back then.

Tristan Skogen

Tristan is currently a student at the University of Colorado, studying history, theatre, creative writing, and education. When he is not busy with school and writing, he’s often found hiking at nearby state parks or practicing music. His current projects include two full length novels (a historical slasher and a fantasy adventure) and a pseudo-musical

retelling of Don Quixote for the stage!

Untitled 2

Shelbey Leco

Shelby Leco

Growing up in Southeast Louisiana, outside of New Orleans, Shelbey was always inspired by nature and art. As a young adult, Shelbey obtained her Bachelor’s degree, at the University of New Orleans, in Interdisciplinary Studies in Urban Society with disciplines in education, English, and anthropology. Shelbey enjoys traveling the country with her friend Ners and dog Boss. She also enjoys creating art and tries to get her work published in as many magazines as she can. Her loved ones constantly ask her what she is going to do with her life. She is doing everything and nothing always.